Artist and director Ulrike Ottinger presents her recollections of living and working in Paris in the 1960s.

Paris Calligrammes: that’s not exactly a movie title that would pique everyone’s curiosity. It’s written and directed by an experimental visual artist and filmmaker named Ulrike Ottinger. I can assure you that she doesn’t take appealing to a mass audience into consideration. She makes films for herself and others who are interested in art and creativity for their own sake.

Ottinger, who turned 80 this year, tells of her experiences in Paris as a young artist, from the time she left her provincial German town in 1962 at age 20, her car breaking down on the way, after which she hitchhiked to the city. She accompanies her narration with a wealth of footage from home movies, newsreels, TV excerpts, still photos, fiction films, and film of life in Paris today. Different sections highlight different aspects of her Paris experience.

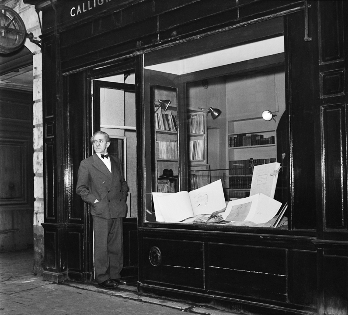

She starts with her discovery of the Librairie Calligrammes, a store specializing in German books owned by Fritz Picard, a Jewish German exile. The word “Calligrammes” was taken from a poem by Guillame Apollinaire, who defines it as a text that creates an image with its letters. By using this word as part of the film’s title, Ottinger is signaling the same artistic purpose of creating an image in the mind through her narration. Anyway, she discovered this German language book store, and the owner, Picard, opened a door for her to a world of intellectual émigrés, including Hans Richter, Paul Celan, and Walter Mehring, that was centered on Dada and Surrealist art and literature. We see an interview with Picard, and hear Mehring recite a masterful poem mourning the deaths of German artists who resisted fascism. This one section is so full of interesting people and stories that I thought this might be the whole movie. But it’s a film of many parts, and although it runs only a little over two hours, it’s brimming with so much incident and detail that I can only marvel that Ottinger has managed to fit it all in.

Other sections cover her friends among the city’s avant-garde visual artists, neighborhoods in which she lived, the vital film scene clustered around Henri Langlois’ Cinémathèque Française, Ottinger’s own progression as an artist influenced by the Dada and Pop Art movements, the left wing politics that pulled Paris intellectuals together in the late ‘60s (and then pushed them apart), and much more. Ottinger was always openly lesbian, and that reality is taken as an assumed basis here, one of the aspects of her life that informs her work.

I found myself stopping the film at times (the great advantage we have in our video era!) to make notes about the film’s numerous anecdotes, remarks, and insights. Ottinger doesn’t try to attain an illusory comprehensiveness, but just by talking about her own experience, her own world, she provides a sense of the excitement and ferment of that time that I’ve never seen equaled.

I would say that this picture is an example of the diary or notebook form within what I call non-fiction film. The word “documentary” is really tired out now, and fails to do justice to the variety we witness in films that are not narrative or dramatic stories. Ottinger uses archival material with an eye towards what you haven’t seen before, avoiding the kind of stock photo montage that we encounter in straight “objective” histories. There’s a lot to take in, and I felt intellectually and emotionally enriched after watching it.