The great director, known for his versatility, was an independent who jumped to whatever studio would hire him at the moment, never with a long-term contract.

The great director, known for his versatility, was an independent who jumped to whatever studio would hire him at the moment, never with a long-term contract.

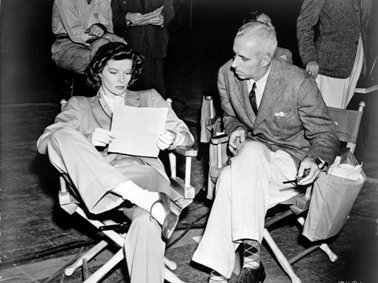

There’s a story that after a certain American movie critic spent some time in Paris in the late 50s reading and listening to the new breed of French film critics, he sent a letter to a critic in the States asking, “Who the hell is Howard Hawks?” It’s true that the French elevated Hawks, a seasoned Hollywood director, into their critical pantheon, but he really wasn’t that obscure. He’d been nominated for an Oscar for Sergeant York in 1941, and he’d helmed plenty of hits through the years. But most film reviewers didn’t pay much attention to directors in the old days, and Hawks was also never identified with a single studio—he was an independent, hiring himself out to whoever wanted his services. This gave him greater creative control than your average Hollywood director, but less publicity.

He directed 40 films, and more good ones than I have time to mention. 1930’s The Dawn Patrol, a World War One air pilot story done for the Fox studio, has a great sense of male camaraderie that became typical of a Hawks picture, with terrific flying sequences and none of the stilted dialogue that you see with most early sound films. (Later he was to top himself with the great air pilot film Only Angels Have Wings.) In 1932, he took on Scarface for Howard Hughes, with Paul Muni playing a criminal loosely based on Al Capone. Of all the early gangster movies, this one has the most taut, physical style, and the most brutally realistic point of view. It was controversial for supposedly glamorizing crime, making it look fun, but that’s really just the exuberance of Hawk’s storytelling, and the dialogue of the brilliant Ben Hecht, who went on to do five more films with Hawks.

Hawks was good at comedies too. Twentieth Century, made in 1934 for Columbia, features John Barrymore and Carole Lombard verbally tearing each other to shreds. Bringing Up Baby, for RKO in 1938, is arguably the screwiest screwball comedy ever, with Cary Grant as a confused paleontologist pursued by the wildly eccentric Katharine Hepburn in her funniest work ever. It didn’t make money, but it’s become a classic since then. Then there’s His Girl Friday in 1940, a version of the old play The Front Page, but with the reporter played by a woman this time, Rosalind Russell. In the lead role, Cary Grant gives his greatest performance, as the slick-talking, totally unscrupulous editor Walter Burns. The dialogue is so fast and funny that you barely have time to catch your breath.

Hawks had a way of attracting good writers. In addition to Hecht, for Warner Brothers in the late ‘40s he had Jules Furthman and the novelist William Faulkner helping him out. To Have and Have Not, and The Big Sleep, both with Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, feature an unforgettable mixture of toughness and cool, especially The Big Sleep, in my opinion the best detective movie ever made. Hawks did plenty of westerns too, including Red River in ’48 with John Wayne and Montgomery Clift, in which he pioneered an overlapping dialogue technique. John Ford saw it and half-kiddingly said that Hawks had somehow tricked John Wayne into actually acting. In his one musical, 1953’s Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, the producer saw Marilyn Monroe performing “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” and said “What? Who knew she could sing?” But that was another thing about Hawks—he could bring an actor’s hidden talents to the surface.

So, who the hell was Howard Hawks? A tall, imposing, distinguished man from the Midwest, radiating a quiet authority, the consummate professional, he is generally considered one of the five or six greatest directors who ever lived.