Todd Haynes tells the story of this influential New York rock band in the cinematic style of the man who discovered them: Andy Warhol.

Todd Haynes tells the story of this influential New York rock band in the cinematic style of the man who discovered them: Andy Warhol.

I’m always interested when a film about a favorite rock band comes out. The Velvet Underground, a documentary about the group that enjoyed brief but unprofitable fame in the 1960s, has the added advantage of coming from a favorite director, Todd Haynes. And, I was not disappointed.

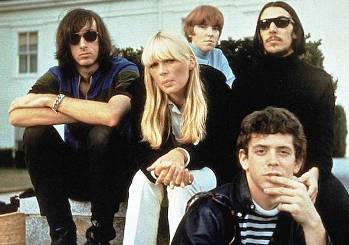

The story begins with two musical artists toiling in relative obscurity. Lou Reed, a Jewish kid from Long Island who played in a doo-wop band in high school, and wrote songs while at college in Syracuse, had started taking drugs in his teens. He’d been in a psych hospital at one point, and his songs reflected dark themes of alienation, addiction, and bisexuality. Then there was John Cale, a young composer and multi-instrumentalist from Wales, who traveled to New York City to be part of the downtown music scene, and met Reed when the latter was working as a songwriter for a recording company. Cale’s experimental style mixed well with Reed’s dark songwriting. They added Reed’s college friend Sterling Morrison on guitar, and Maureen Tucker, the sister of another Syracuse friend, on drums, and called themselves The Velvet Underground.

They were playing in a bar when someone who knew Andy Warhol saw them. Warhol came himself to listen, and put some of his cultural weight in to give them more attention. Later, when a beautiful singer and model from Germany with the stage name “Nico” showed up at Warhol’s art factory, he persuaded the Velvet Underground to make her a part of the group. They recorded an album on Verve Records, with Warhol’s painting of a banana on the cover, and then Warhol had them tour with a light show in 1966 and ’67, these shows becoming legendary as the “Exploding Plastic Inevitable.” This was the beginning. The film covers the entire eight years of their career.

There are excerpts from interviews, including some from group members who are now deceased, and those accompany a lot of historical footage of the group. And all this is quite standard for a documentary, but Haynes presents the film in a style that simulates the New York avant-garde cinema of the 60s, and especially that of Andy Warhol.

Haynes uses lots of split screen, sometimes with footage in one section and interview material on the other, but often with more than two sections in the split, and a constant swirling visual effect, mixing painting, sound, photographs, and talk, which strongly evokes the period of the 1960s and early ‘70s, in which the story took place. We learn a lot about Warhol’s methods and the people in his orbit. We learn about Nico walking away to do other things eventually. We learn how the chemistry between Reed and Cale went badleading to Cale’s exit and Reed’s refashioning of the group. And all this is conveyed by Haynes’ uncompromisingly flamboyant style. Any movie about the group with this material would be good, but this wild aesthetic form adds immeasurably, I think, to the film’s power.

At the time, the Velvet Underground only had a cult following. In the era of peace, love, hippies, and pot, their songs about the underclass and urban angst, and harder drugs like heroin, were not a best-seller. But years later, after Reed had made a successful solo career, these early albums became enormously influential in rock music, and remain so to this day. Now we have the film The Velvet Underground, and it gives us a satisfying taste of what it was really like to be there.