A man seeking refuge in a coastal city of 1977 Brazil doesn’t know that two men have been hired to kill him, in this brilliant portrait of life under dictatorship.

The Secret Agent is the name of a new film by Brazilian writer and director Kleber Mendonça Filho. Right from the start with the title, we have ambiguity. It’s not a spy movie—no one is engaged in espionage. Rather, it’s presenting the experience that is prompted by the idea of a secret agent: always be on your guard, danger lurks around the corner, conceal who you are. In historical terms, it’s about living under a dictatorship and trying to be human in the midst of cruelty.

The story opens in Brazil in 1977, during the latter period of the military junta’s long repressive rule. A man in a yellow Volkswagen stops at a lonely gas station in the middle of a desert near the city of Recife. About twenty yards away, there’s a dead body lying under a piece of cardboard. When the man asks the guy at the gas station about it, he says someone tried to steal some motor oil two days ago and was shot by the night attendant, and no one has yet come for the body. Two policemen then pull up, but rather than do anything about the corpse, they harass the Volkswagen guy, searching his car for drugs, and finally accepting a bribe to leave him alone. This strange opening sequence, drenched in gallows humor, is like a little prelude to the main plot of the movie, illustrating the indifference and absurdity of this time of violence.

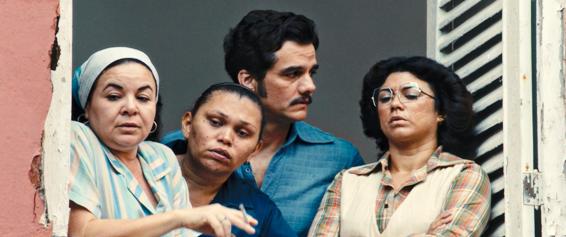

Our main character, Marcelo, played with a pensive diffident charm by Wagner Moura, goes to Recife and is welcomed by a chain smoking little old lady who’s been expecting him. She helps him set up his stay in her apartment building, introducing him to other interesting inhabitants, including one with whom he’ll have a casual love affair. Gradually we realize that everyone in these apartments is hiding from the authorities for one reason or another. And Marcelo, as it turns out, is not his real name. He’s actually Armando, and he’s fleeing some unnamed trouble in Sao Paolo. He also wants to see his young son, who lives in Recife with his late wife’s parents. When he visits him, the boy is drawing pictures of sharks, and he’s excited about seeing the movie Jaws, which is playing in town. But Armando says he’s too young to see that.

Cut to a scene near the docks, where in the presence of the police, a dead shark is cut open and a human leg is pulled out. In a Mendonça Filho film, surrealism can emerge at any moment. Later in the movie we witness a disembodied leg on the loose, kicking people to death in a park. The cinematic language equates such hysterical urban legends with the real terror of state-sponsored disappearances.

All the film’s events and plotlines double as metaphors for other things, including the act of filming itself. Armando’s father-in-law owns a theater, and this evokes a film-within-a-film motif. Later, a lengthy part of the movie, in which hit men hired to kill Armando by someone he’d worked for, stalk him at the city’s department of records, turns into one of the scariest and most thrilling action-suspense sequences in recent years. But thrills are not the point, which is something the director underlines, after meticulous attention to tiny details, by dropping a crucial event on us suddenly, through a mere photograph.

The Secret Agent is a heartbreaker, a beguiling poem of conscience that comes full circle to our present moment. It’s a film of reckoning.