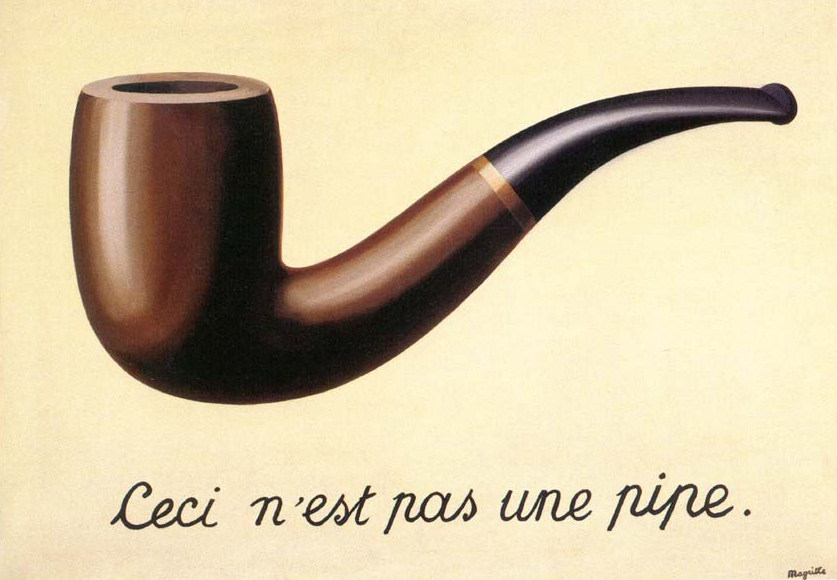

Every once in a while a book crosses the Weekly Green desk that provides a counterpoint to the way we in our industrialized, consumption-based society experience and deal with the world we live in. Just about a year ago we reviewed “The Spell of the Sensuous” by David Abrams, which argues that we lost touch with our environment – and by the same token with the core of our own being – because of the intermediacy of our phonetical writing system, in which something is not represented directly, as with a pictogram, but by a representation of the utterance we associate with it. The thing becomes the word we have for it, which is like mistaking the map for the land.

The discussion whether language is a reflection of the way we think, or if it is the other way around, has been going on for centuries and is as near to a conclusion as the one about the chicken and the egg. But it is evident that there is a close reciprocal relationship. If our language does not actually shape our thought processes, it does certainly provide a good clue to them.

Take the word ‘green‘. If we look at a tree, we perceive it as ‘green‘. The tree next to it we also perceive as green, as well as the pasture it stands in. But the ‘green‘ of a tree is not just one green. It actually shows countless shades of green, which are influenced not only by the intrinsic hues of each individual leaf, but also by a multitude of external factors, the reflections from its surroundings, the weather and the time of day. As a matter of fact, we even think of a tree as ‘green‘ at night when it actually blueish-gray.

We perceive things in the context of their similarity to other things, unconsciously applying categorizations that have formed over millennia. This ability to generalize is at the root of the tremendous accomplishments of modern society. But at the same time, it prevents us from perceiving something simply as it is, at the particular moment and place we encounter it.

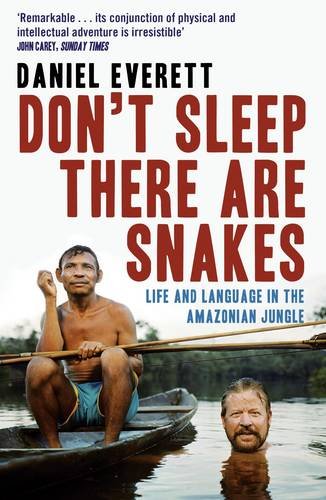

What if we would not have a word for “green”? As strange as it may seem, there are people in the world that do not, and linguist Daniel Everett’ describes one such tribe, the Amazonian Piraha, in his 2008 book “Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes”. In his decennia-long field study of this isolated tribe, Mr. Everett found that not only does their language lack color words, but also words for numbers and several other features that would seem indispensable to us.

What if we would not have a word for “green”? As strange as it may seem, there are people in the world that do not, and linguist Daniel Everett’ describes one such tribe, the Amazonian Piraha, in his 2008 book “Don’t Sleep, There Are Snakes”. In his decennia-long field study of this isolated tribe, Mr. Everett found that not only does their language lack color words, but also words for numbers and several other features that would seem indispensable to us.

He attributes this to a fundamental tenet of their culture he calls the ‘immediacy of experience’. To the Piraha, anything beyond the immediate is unreal and so they do not categorize or speculate about the future or the past like we do. They even lack a creation myth, because there is nobody around who can give a first-hand account of it. By the same token, they do not have any tradition and even their ability to express family relationships is extremely limited. If they have to describe a color, they do so by comparison to something of which they have immediate knowledge. “Green” would be “like unripe fruit”, for instance.

This constraint to the bounds of the present, Mr. Everett suggests, underlies the remarkable contentment and joyousness of the Piraha. They do not suffer from anxiety or depression. They are perfectly happy with their way of life, harsh though it may seem to us, and vigorously resist any attempt to change it.

We cannot be like the Piraha, obviously, as much as we cannot go back to living in caves, even if we would want to. We are much too far along the path we have picked to turn around. But we could learn from them look at things without the filter of the names we have given them, if only for a moment. If Mr. Everett is right, that moment might provide a contentment and joy surpassing any shopping spree.

(Broadcast 4:02)