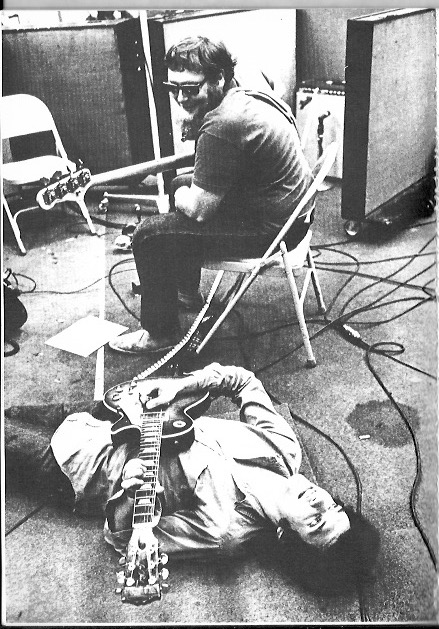

What a cool look behind the scenes on these historic recording sessions for Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited from acclaimed bass player and former Tucson resident, Harvey Brooks.

Highway 61 Revisited: 50 Years Ago Today

By Harvey Brooks

It was July 28, 1965. I was playing a gig at the Sniffin Court Inn on East 36th Street in

Manhattan. During a break, I went next door to eat at the Burger Heaven, when I got a phone call

from Al Kooper.

I’m playing on this album with Bob Dylan and they need a bass player – are you doing anything?

That phone call would change my life.

The next day — 50 years ago today — I drove from Queens to Manhattan. After parking my car

in a lot on 54th Street, I was soon in an elevator on the way to play for Bob Dylan’s Highway 61

Revisited album at Columbia Studio A at 777 Seventh Avenue. I opened the door to the control

room, took a deep breath and entered.

The first person I saw was Albert Grossman, Dylan’s manager. Grossman had long gray hair tied

in a ponytail and wore round, tinted wire-rimmed glasses. I thought he looked like Benjamin

Franklin. A thin, frizzy-haired guy dressed in jeans and boots was standing in the front of the

mixing console listening to a playback of “Like a Rolling Stone.” I assumed it was Bob Dylan,

though I didn’t know him or what he looked like at the time.

When the music stopped, Grossman asked, who’re you? I told him who, what and why. Dylan

quietly muttered “Hi” and went back to listening. Al Kooper then came in to make the official

introduction. It was all very cryptic and brief.

I walked into the studio, opened up my case, took out my Fender bass and started to tune. My

instrument was strung with La Bella flat wounds, which I still use. I plugged in the Ampeg B-15

amplifier which was provided by the studio. It sounded warm and percussive. The B-15 was my

gig amp as well. Now I use Hartke amplifiers exclusively.

Though I was only 21-years-old, I had already played many club gigs with a range of different

performers. I had worked with varying styles and felt I could adapt to about anything on the fly.

For that reason, I was comfortable in the studio and was ready for anything Dylan could throw

my way.

Suddenly, the studio door burst open and in stormed Michael Bloomfield, a moving ball of pure

energy. He wore penny loafers, jeans, a white shirt with rolled-up sleeves and had a Fender

Telecaster hanging over his shoulder. Bloomfield’s hair was as electric as his smile. It was the

first time I had met or even heard of him.

The other players on the session were Bobby Gregg on drums, Paul Griffin and Frank Owens on

piano and Al, who on the “Like a Rolling Stone” recording session two weeks earlier, had nailed

his position on organ

At the first session, Joe Macho Jr. had played bass. He had been replaced by Russ Savakus who

Dylan didn’t like either. Dylan wanted someone new for the rest of the sessions. Kooper

recommended me to Dylan. What Dylan needed was to be comfortable with his bass player.

Kooper knew I had a good feel and adapted quickly to any situation.

For Dylan, it was not enough to be a skilled studio musician. He wanted musicians who could

adapt quickly to his style. In talking to Bob, I admitted that I hadn’t heard any of his music

before the session, but was really impressed by “Like a Rolling Stone,” which I first heard when

I walked into the studio.

“Well, these are a little different,” Bob responded. I assumed he meant from his past work, but

Bob was bit vague. He gave me a kind of crooked smile and then lit up a cigarette.

Tom Wilson, who had produced Like a Rolling Stone a couple of weeks earlier, also was replaced

for unknown reasons. The new producer was Bob Johnston, a Columbia staff producer from

Nashville who was already producing Patti Page when he got the Dylan assignment.

Johnston had a “documentary” approach to producing that allowed him to capture fleeting

moments in the studio. He was frustrated by the technical bureaucracy at the Columbia studio

and ordered several tape machines brought into the control room so he could keep one running at

all times in order to capture anything Dylan might want to keep. That tactic worked quite well

for an artist like Dylan.

Though the first session for Highway 61 Revisited had been only about two weeks earlier, a lot

had happened in the interim. Like a Rolling Stone, recorded at the first session, had been released

and caught on like fire.

Only four days earlier, Dylan had been booed by the crowd when he had gone electric at the

Newport Folk Festival. It was a pivotal time in his career. He was beginning the transition from

being a “pure” folk artist to a rock and roll performer.

Now we were at the second session, my first, uncertain of what was on Dylan’s mind. In a few

minutes, he came out of the control room and started to sing the first of three songs we would

work on that day. Johnston had setup three-sided baffles, leaving the side that faced the band

open so we could see him.

Dylan sang the first song, Tombstone Blues, a few times. There were no chord charts for anyone.

It was all done by ear. As a habit, I made a few quick chord charts for myself as I listened to him

perform the song. Everyone focused on Dylan, watching for every nuance. Then, the band went

for it.

As we began recording, Dylan was still working on the lyrics. He was constantly editing as we

were recording. I thought that was a really amazing way that he worked. His guitar or piano part

was the guiding element through each song. Every musician in that room was glued to him. We

would play until Dylan felt something was right. His poker face never revealed what he was

thinking.

It might have taken a couple of takes for everyone to lock in. There were mistakes, of course, but

they didn’t matter to Dylan. If the feel was there and the performance was successful, that’s all

that mattered. In real life, that’s the way it is. If the overall performance happens, there is always

something there. Bob would go into the control room and listen. Bob Johnston may have been

the producer keeping the tape rolling, but it was all Dylan deciding what felt right and what

didn’t.

Michael Bloomfield’s fiery guitar parts accented Dylan’s phrasing. He was a very explosive

guitar player and didn’t settle back into things. He was aggressive and a little bit in front of it.

My goal is finding a part that makes the groove happen. Dylan set the feel and direction with his

rhythm and my bass parts reflected what I got from him.

Most of my early playing experience had been in R&B bands that performed Wilson Pickett and

Jackie Wilson, or tunes by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. Playing with Dylan created a

totally new category. I call it “jump in and go for it.”

Next, we recorded It Takes a Lot to Laugh and Positively 4th Street the same way. Masters for

the three songs were successfully recorded on July 29. Tombstone Blues and It Takes a Lot to

Laugh were included on the final Highway 61 Revisited album, but Positively 4th Street was

issued as a single-only release.

At the close of the session that first night, Dylan attempted to record Desolation Row,

accompanied only by Al on electric guitar and me on bass. There was no drummer, as Bobby

Gregg had already gone home. This electric version was eventually released in 2005, on The

Bootleg Series Vol. 7 album.

Our producer had a love of and even a bias toward Nashville musicians. It became an underlying

topic during the entire session about how good they were. He kept talking about how cool

Nashville is. With his comments, I felt it was disparaging to us. I felt Johnston thought of us as

New York bumpkins in a way.

This Nashville bias played into Desolation Row. I thought the version without drums that I did

with Al that night was slower and definitely more soulful. We really liked it. Clearly, Johnston

thought otherwise. On August 2, five more takes were done on Desolation Row. However, the

version of the song ultimately used on the album was recorded at an overdub session on August

4.

This time, Johnston’s personal friend, Nashville guitarist Charlie McCoy, who was visiting New

York City at the time, was invited to contribute an improvised acoustic guitar part. Russ Savakus

played upright bass. We were gone by the time the final take was recorded.

When I left the studio after the final session, I didn’t have a sense of whether or not we had

created a hit record. I did know, however, that all the songs felt good. They felt solid. I now

understand that’s why Highway 61 Revisited was a successful record. Bob got it. In all the takes

he chose, he made sure he got what he wanted from each song. It’s an amazing talent that really

knows what they want.

###